The Zombies of Breichdykes

A sombre history of Briechdykes

Freeport, the Five Sisters and the surrounding wilderness that was once the lands of Breichdykes farm.

F21003 - first published 2nd April 2021

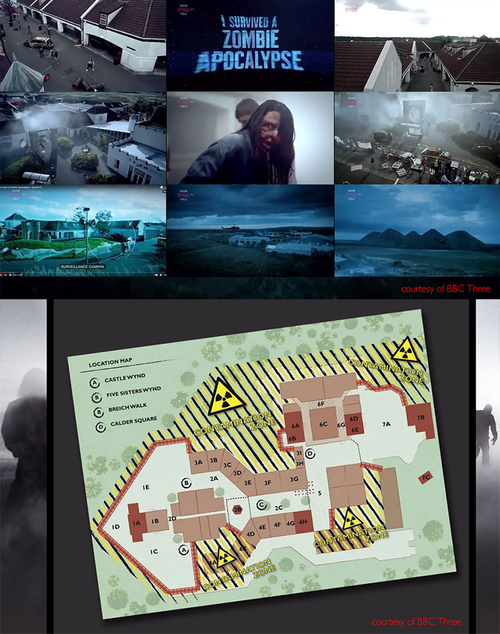

In 2015, thirteen young people endured a horrifying ordeal as they sought shelter from terror among the abandoned remains of Munro (or Freeport) shopping village. It was said that a new type of 5G phone signal caused the genetic mutations that spawned a worldwide pandemic of a terrifying new virus. Once infected, its victims underwent a slow and painful zombification, their broken and decaying bodies condemned to a miserable existence in their daily quest for human flesh. A sorry hoard of flesh-eating zombies had assembled in the sinister misty boglands that surrounded the shopping village, awaiting opportunity to break their way through the barricades and enjoy their gory feast. Only four of thirteen survived to the final episode of BBC3’s reality TV game show, and were able to claim that “I survived the Zombie Apocalypse”.

The show ran for only one season, (perhaps the idea of a global pandemic of a terrifying new virus seemed a little too far fetched?), but was compelling television. Much of its impact was the result of the gloomy post-apocalyptic landscape which featured throughout and created a constant sense of unease and foreboding. And where else but in West Lothian could you find an abandoned shopping centre, set within a watery mire and overshadow by the looming mass of five giant bings?

The strange case of the flesh-eating zombies was just one small episode in the strange story of what became known as Freeport leisure village – an out of town shopping mall built in the middle of nowhere which enjoyed only a brief life. Opened with all due razzmatazz in 1996, it failed to become established as a designer shopping outlet, and never realised the ambition to become the heart of an ambitious leisure complex. The doors of the village closed in 2004, but it remains guarded and largely intact, visited only by the occasional zombie.

More strangeness surrounds the land on which the shopping village was built. One might think that this wet expanse of reeds and tussock grass was a wilderness that had never been tamed by man. In truth this was once the rich pasture and arable lands of Briechdykes farm, and home to a small community. Why the lands were allowed to revert back to wilderness remains strangely unclear, but where dairy cattle once grazed is now home only to wild birds, deer and the restless zombies.

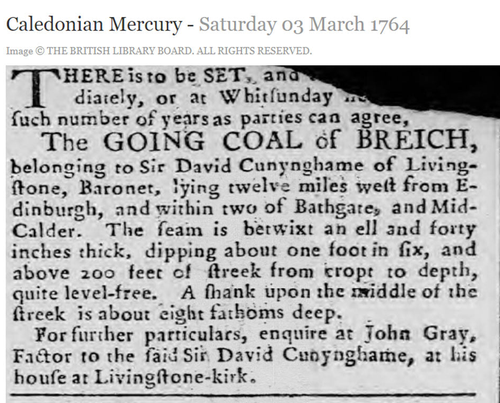

250 years prior to the zombie apocalypse, the lands of Briechdykes, and most of the rest of Livingston parish, remained the property of the local Baron, Sir David Cunynghame. In 1764 Sir David advertised for parties to work coal at Briech (most likely at Breichdykes) describing the seam as “between an ell and forty inches thick” with a “shank in the middle of the streek about eight fathoms deep” (don’t you love the language?). These would have been one of the earliest significant coal workings in this part of the county, but seem to have been abandoned by about 1830. The first detailed Ordnance Survey map, printed in 1855 shows only a number of disused shafts, and only faintest of humps and dimples in the ground now remain at the sites where men would have been lowered into the underworld

Sir David sold the lands of Briechdykes in 1791, and it is perhaps at this time that the land was fenced, fertilised and drained as part of the agricultural improvements that were then transforming the countryside. William Forrest’s map of 1818 shows the layout at that time. Breichdykes farm is schematically shown as cluster of buildings with a number of kitchen gardens associated with them. Accounts describe this as an “excellent steading of houses” which was probably home to several families. Other accounts confirm that the land had been thoroughly drained with a small part under arable cultivation and the rest under pasture. The nearby coal pits are clearly marked. The road serving the farm continued southwards, zig-zagging down the steep valley side, passing a small building at the hairpin before fording the Breich water close to Briech corn mill, and joining the Addiewell road

Strangely no trace of this through road appeared on the 1855 Ordnance Survey map, although it showed solid farm buildings at Briechdykes, including a circular horse gin to power a mill, and a series of well laid out fields. The lands of Breichdykes and Westwood were bought in about 1844 by the Steuart family, who had previously worked the coal reserves beneath their estate at Carfin. It was probably Captain Robert Steuart of Westwood who was the driving force behind exploiting the mineral wealth of Breichdykes. After failing to obtain worthwhile offers to lease the mineral rights, he chose to work the oil shale on his own account and build his own oil works somewhere in the area of Briechdykes farm.

The precise location of this first Westwood oil works is another mystery, as the buildings, and the mineral railway that linked them to the Caledonian railway, are not marked on any known map. The route of this mineral railway can be faintly made out on old aerial photographs, although much of the evidence on the ground was obliterated with the construction of Freeport. On the steep valley sides of the Briech water, fused blocks of red blaes still protrude through undergrowth marking tipping points, radiating our like the fingers of a hand, where spend shale from the oil works was dumped into the valley.

The oil works surely lay somewhere between the railway and the tip, but there is no evidence on the ground or on maps to suggest it’s precise location. Similarly it’s not know which of the little pits and diggings scattered around Breichdykes supplied oilshale to the works.

The area in 1818, showing the settlement of Breich Dyke, the coal pits and road winding down into the valley of the Briech Water

The farm in 1855, by which time the road to Breich Mill and Addiewell had mysteriously disappeared

The oil works opened in about 1866 but closed just five years later Like many other early oil works it was the victim of falling oil prices. When Breichdykes farm was offered for let in 1874, it was described as “specially adapted as a dairy farm” and “thoroughly tile drained”, with a dwelling house and steading refurbished only two years previously. It also offered the amenity of a private railway siding – presumably the branch line that had served the oilworks. It’s hard to imagine that milk produced on the farm would have been considered sufficient traffic to retain the railway for long.

Following the collapse of Robert Steuart’s dream of becoming an oil tycoon, he let the rights to the minerals beneath his estate to the Young’s Paraffin Light & Mineral Oil Co. Ltd. Young’s worked the Fells shale that lay beneath Briechdykes from pits in the eastern part of the Westwood estate. These were exhausted and abandoned by about 1881.

It is perhaps these workings from Westwood No.12 and 13 pits that explain Breichdykes farm’s return to wildness. The workings lay little more than 20 metres beneath the surface, and only a small amount of subsidence would have been sufficient to disrupt land drains and undo all the good work achieved by earlier generations who had improved the land. It seems that the farmers finally gave up on the ongoing struggle to repair drains and abandoned the area to agriculture. By 1914 only one small part of the farmhouse remained habitable. Since then, a century of moss and reed have built up to obscure many traces of the past

It’s hard to imagine what the future holds for the lands of Breichdykes. As the fortunes of the shopping centre waned there were bold plans for an indoor ski centre, a golf course, an ornamental lochan and much more besides, but these have come to nothing. It’s as if sadness and failure in ingrained in the land; a strange place of grand schemes, broken dreams and marauding zombies.