Well. Well, Well.

Letham Well and other healing wells.

View from St Mungo's well Midcalder towards Letham farm, glimpsed in the distance (left) between the two blocks of trees. St Mungo's was described in 1853 as " a dry-stone built well, situated in the grounds of a private house". " It is located on the slopes of an embankment, still contains water, and is now enclosed by a fence."

The photograph dates from some time after 1935, when the lands of Letham farm were divided into 22 small holdings.

F19018, first published 27th April 2019

Springs and wells were once regarded as places of spiritual and mystical significance. Perhaps the emergence of waters from beneath the ground was considered a link to an unseen underworld. Rituals at such special places might involve offerings and sacrifices, with the hope of being rewarded with good luck or a return to sound health. Such ancient customs and folklore were absorbed into Christian worship, and old beliefs became expressed in the language of saints, healing waters, and holy miracles. Special ceremonies at springs and wells often took place at the start of May, continuing the old Celtic tradition of Beltane. Coins, pins, flowers or stones might be left as tokens of devotion, while scraps of clothes and fabric might be tied to nearby trees as personal links to those seeking relief. Of course the tradition of wishing wells continues to this day, although usually relegated to garden ornaments overseen by smiling plastic gnomes

Such old beliefs were part of folklore by 1798 when James Gray wrote his description of Livingstone parish for the first statistical account. At that time the traces of a fortified tower, once part of a royal hunting estate, still survived at Newyearfield. Gray reported that the water from a nearby spring-well was said to provide a specific cure for serosula “when applied by the Royal hand upon a New Year's morning before sunrise”. No doubt this was said with a wry smile; as the likelihood of all of these occurrences coinciding would seem extremely unlikely. This humorous anecdote was repeated in the new statistical account of 1843, which also commented that the tradition had the benefit of encouraging people to rise early and wash regularly!

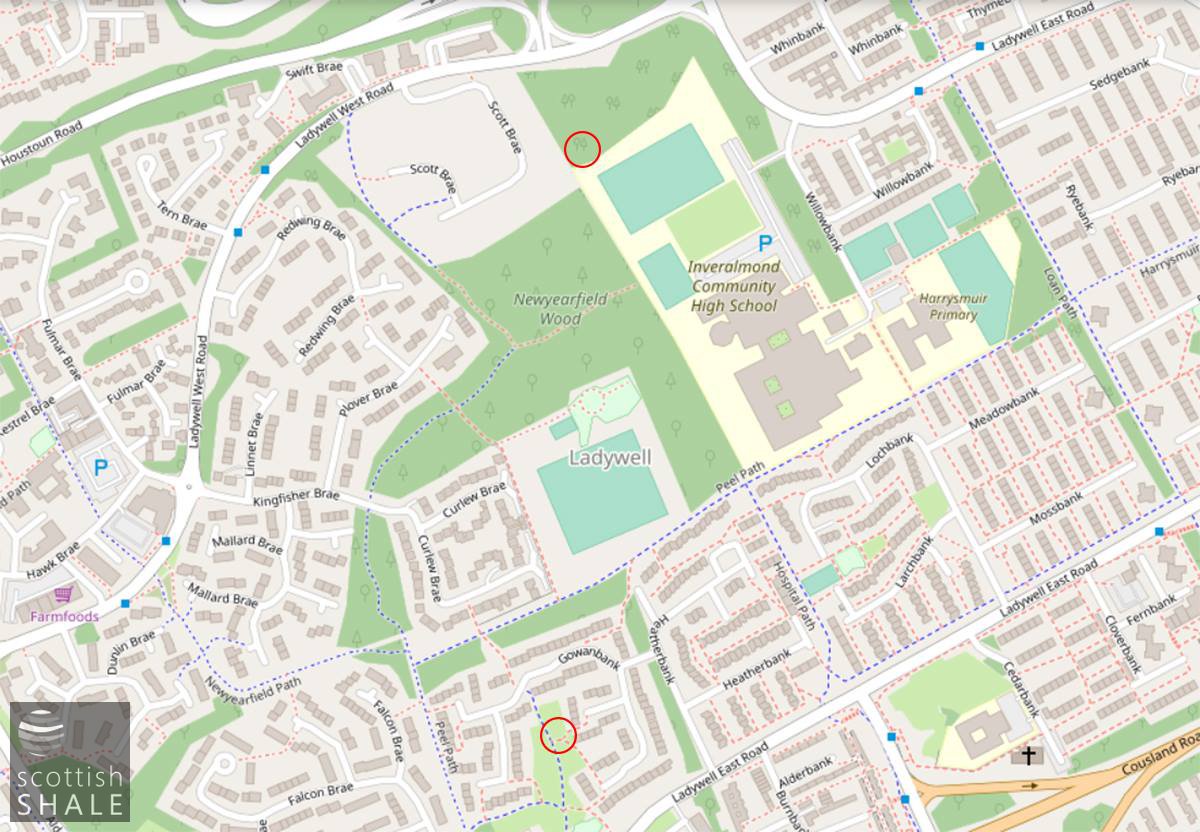

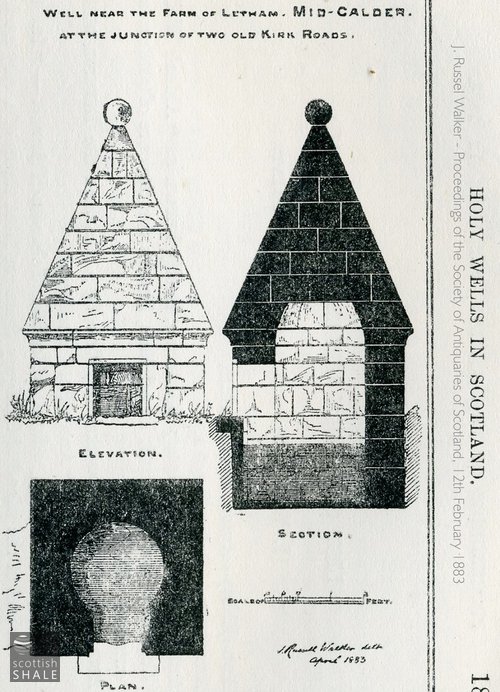

The Ordnance Survey name book compiled in1853 describes two wells near Newyearfield; the Rose Well and the Lady Well. It was the waters of the Rose Well that had been said to be effective against the “Rose” or “Kings Evil”, if applied early on New Year's morning, By then the well “was partly choked with weeds and appears to have been partly enclosed in stone work”. It was a “fine spring with a small stream always issuing from it.” The well was missing from the 1895 and subsequent OS maps. The site is now on the edge of woodland, immediately east of Scott Brae, and a scatter of stones from a collapsed boundary wall might include some remains of the well. The Lady Well was said (in 1853) to be of modern formation; a small well enclosed in stonework from which a small stream issues from it and flows south. The natural basin surrounding the well was retained as green space when the housing of Gowanbank and Heatherbank were constructed by the new town development corporation

In the age of enlightenment, medical men sought a scientific understanding of the healing properties of spring water. At that time there was limited understanding of chemistry, little concept of germ theory, and no effective treatment for many terrible infections. Some hoped that special properties of certain spring waters could be effective against common diseases such as tuberculosis. Symptoms of the disease, were referred to variously as scrofula, serosula, the King's evil, and other terms, and led to terrible disfigurement, progressive debilitation and death. In the absence of effective medicines, water treatments, particular the use of sulphur-rich spring waters were hoped to provide some benefit.

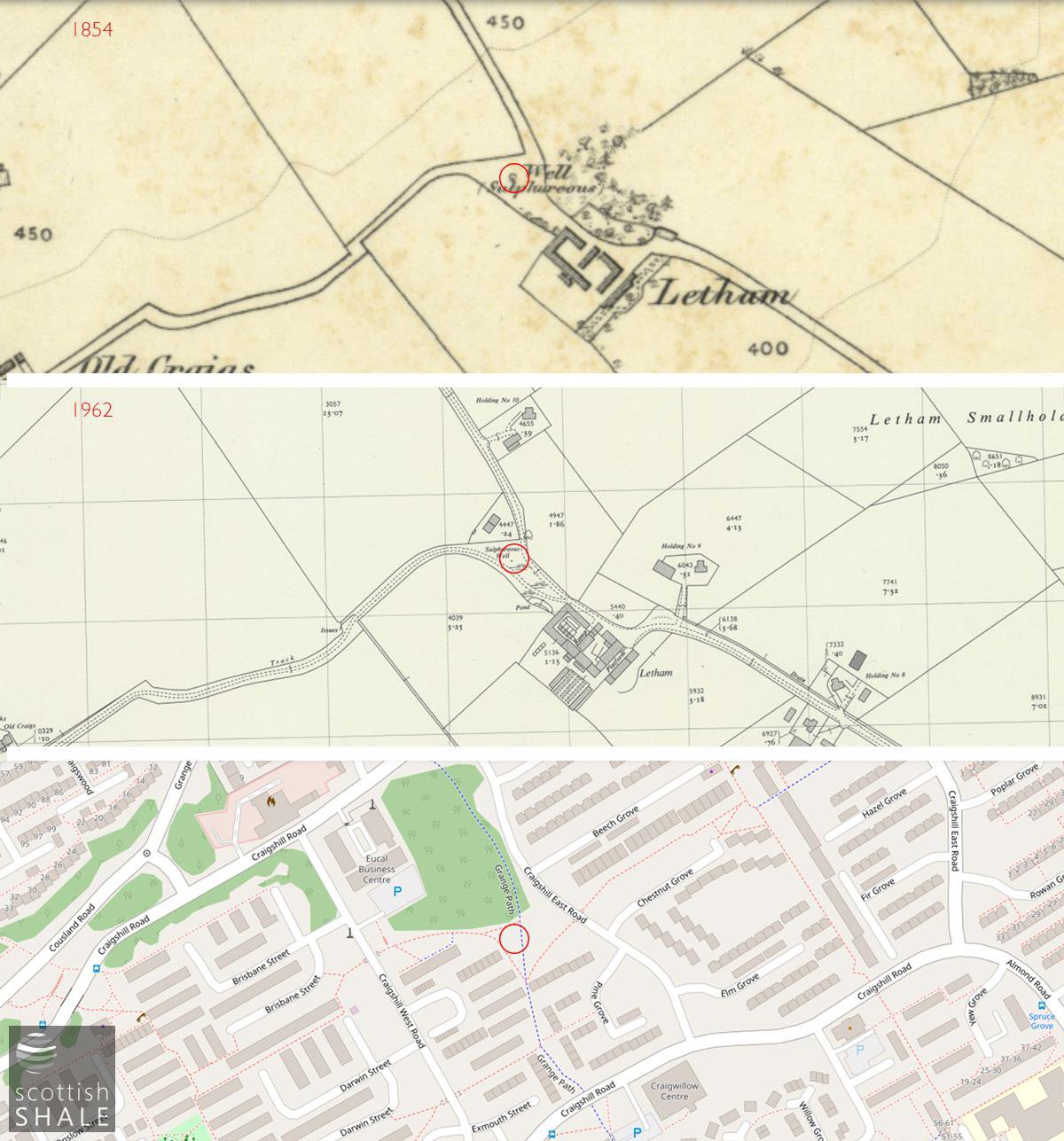

One such foul-tasting sulphur rich spring occurred close to Letham farm, and in about 1760, Midcalder surgeon Dr. John Lamont promoted construction of a stone well to allow better access to the cold clear spring water that tasted strongly of rotten eggs. It was frequently said that the water had similar qualities to those at Harrogate, however Letham was never to develop into a fashionable spa resort. The stone enclosure around the well was described as “a pleasing and appropriate structure” and survived in a ruinous state into the 1960's, Despite listed building status, the remains of the well seems to have been swept away with construction of new town housing at Craighill; a rather surprising decision given Livingston Development Corporation's usual respect for local history. However the routes of paths and green spaces around Canberra Street and Pine Grove still reflect the layout of the former landscape where “two old kirk roads meet”.

While the waters of Letham are lost beneath the concrete of urban Livingston, several other sulphur-rich springs still remain in West Lothian. One such example is the Bullion Well, at the foot of Tar Hill close to the village of Ecclesmachan. As in Letham, the sulphureous waters seems likely to be the result of volcanic action on seams of oil shale many hundreds of millions of years ago. The “well” is now little more than a trickle of water amongst marshy ground, but retains just the slightest hint of rotten eggs. Above right: The well at Letham, the ruins of which survived into the 1960's.

Looking towards the housing of Canberra St. Craigshill. The sulphureous well would have been located close to the patch of burnt ground in the centre of the picture.

Woodland in Craigshill near the site of Letham well, the paths following the layout of an earlier landscape "where two old kirk roads met".

Site of the Lady Well, marked by the black litter bin in the middle distance.

Probably site of the Rose Well, marked by the discarded nappy, with the houses of Scott Brae in the background.

Collapsed walls and rubble at the site of the Rose Well.

View from the Tar Hill, looking south towards the Pentland. The patch of reeds in the centre mark the route of spring water emerging from the base of the hill.

The Bullion well-spring, cloaked in luxuriant grass and gorse.

Beneath the gorse, the waters of the Bullion spring emerge, with just a hint of rotten eggs.