Southrigg Bogies and Butterflies

Stories of the Southrigg collieries

F22016 - first published 18th September 2022

If you head south from the West Lothian village of Westrigg towards the West Lothian village of Greenrigg, you need to cross a little part of Lanarkshire that seems to bite into the outline of the West Lothian. Much of the intruding tongue is a boggy and waterlogged land that has never supported much agriculture. It is now largely covered in conifer plantations and a more recent crop of wind turbines. Construction of the M8 in the 1970's has cut across all paths that once ran from north to south, leaving the land – especially that around Southrigg farm - as a little-visited wilderness of reedy pools and moss set among blocks of impenetrable forest. You are always within earshot the motorway, yet you still feel strangely remote.

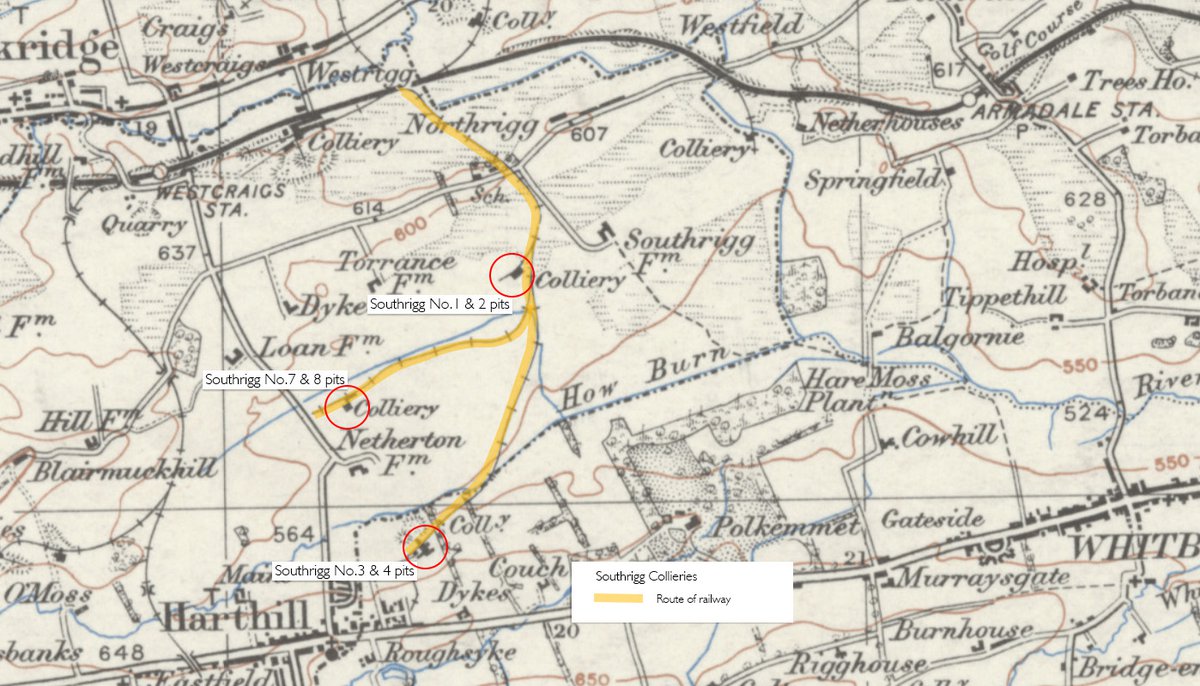

Once this was a very different landscape of collieries and connecting railways. The seams of coal found here were similar to those mined in the Armadale area, but lay much deeper and remained unworked until the 1880's. Southrigg No. 1 pit was begun in 1883 on a site about three quarters of a mile south of the Bathgate to Airdrie railway to which it was linked by a new mineral railway. The pit was a bold venture by George Moir, a Glasgow coal merchant who had no experience of operating coal mines. It bankrupted him within a couple of years and ownership passed to Alexander M. Graham, a practical engineer who “devoted himself most assiduously” to his duties as a coal master.

The firm of James Nimmo & Sons Ltd was one of the leading coalmasters of the time with pits in Lanarkshire, Stirlingshire and Fife. The company recognised the potential of the deep reserves of Armadale coal that lay beneath the western margins of West Lothian and ultimately operated a string of pits extending from Blackridge to Fauldhouse. Alexander Graham agreed to sell his pit to Nimmo & Co, in 1898 but shortly after signing an agreement in the lawyers' office the poor man was “seized with a fit of apoplexy” and died within the hour. He was only 47. A few years later Nimmo & Son became part of the huge coalmasters conglomerate; The United Collieries Ltd.

The lack of local housing made it difficult to find staff for the remote Southrigg No.1 pit and most workers faced a major trek across fields and moors at the start and end of each shift. On one occasion the coal company was forced to pay compensation to a local farmer for the damage caused by the hundreds of pit boots that regularly trampled across his fields. The labour crisis became so acute that special workers trains were laid on to transport miners from the Coatbridge area to work the Southrigg pits.

In around 1900, the colliery company took over the mineral railway to No.1 pit, built a shed to house their colliery pugs, and extended the line a further mile southward to serve a new No. 3 pit, sunk at a site a little to the east of Harthill. The line followed a mainly straight course and steady incline down into the valley of the Almond, giving fine views across to the Polkemmet estate. Here in May 1924, three lads from Harthill thought it would be fun to take a platelayers bogie from No.1 pit and set it off down the long hill to No.3 pit. It's not recorded whether they jumped on for a wee hurl, but it would have been a great thrill ride. No damage seems to have been done, but each was fined 6d (with the option five days' imprisonment). Southrigg No.3 colliery developed as the most successful of the Southrigg pits, employing over 400 at its height, and forming the nucleus around which the new village of Greenrigg developed.

In around 1903 further pits (Southrigg No.7 and 8 ) were sunk in the lands of Netherton farm, about half a mile west of No.1 pit, and a branch line was extended to serve it. The pits (usually referred to as Netherton colliery) quickly encountered difficult geology and a great influx of water. The tiny pit bing that survives on the site shows how little coal was brought to the surface before the company cut their losses and abandoned the pit in 1909. The following year the pithead chimney stalk was struck by lightning and damaged so seriously that it had to be demolished. Only a handful of staff were on site at the time to overseeing pumping operations and none suffered injury, although a bricks and mortar were scattered over a large area. Pumping operations continued at No. 7 & 8 pit to drain neighbouring workings and the troublesome influx of water sometimes proved useful at times of drought. In the particularly thirsty summer of 1911, pipes were laid to direct pit water to reservoirs in order to replenish the public water supply. The solid brick under-building of the winding house still survives as a substantial memorial to a wasted investment.

The underground workings of No. 3 & 4 pits were extended to link up with Greenrigg pit, but throughout its history the pit was plagued by water ingress and drainage problems arising from the undulating nature of the seams. In 1939 it was decided to abandon the Southrigg pits and sink a new pit some way to the West to better access remaining coal reserves. The long mineral railway worked by United Collieries' little engines seem to have closed at that time.

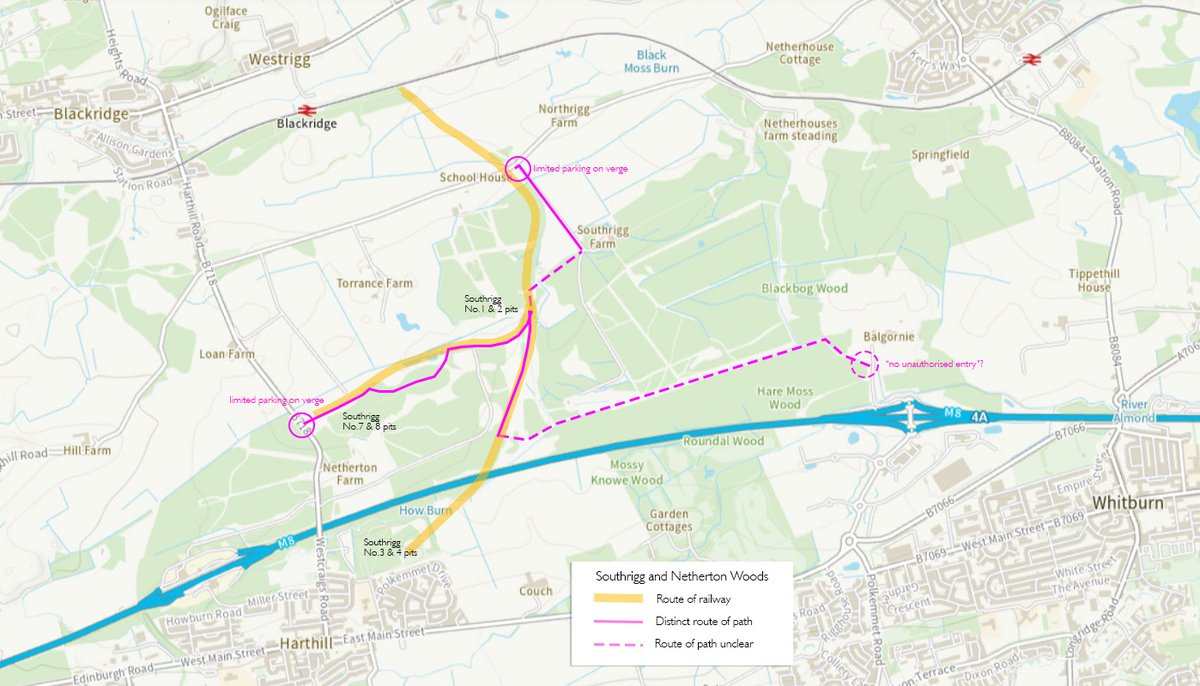

A sign beside the Harthill to Blackridge road, close to the ruins of No.7 & 8 pits, welcomes walkers to Netherton woods. There's a rough lay-by that can hold a couple of cars and a path marked out by a series of dilapidated signposts. A little burn that once ran beside the railway now forms a series of attractive reedy pools and it is necessary to follow a winding path through the trees before being able to return back to route of the railway. There's a shallow cutting then a good embankment that curves to the north, meeting up with the course of the railway to No.3 pit close to the wooded bing of old No.1 pit, that closed back in 1914. In this overgrown and little visited place you are confronted with a rather incongruous sign welcoming you to the Southrigg woodland and a map showing a optimistic network of paths and woodland pools. In summer at least, it is difficult to find a route northward beyond the welcome sign due to a wall of densely packed trees and bushes. It is possible to beat a path through this undergrowth, but there are hidden ditches and perilous marshes. Eventually you should reach the track serving the Southrigg wind farm that follows a straight course north to the Northrigg road, close to where the colliery pug and its rattling train of coal wagons once cross the road.

Alternatively you can turn your back on the “welcome to Southrigg woods” sign and instead head south following the straight course of the old railway heading downhill towards Greenrigg and Harthill. This is the long steady hill on which the three lads and a bogie created mischief nearly a hundred years ago. The well-drained raised course of the railway, and perhaps also the alkaline slag ballast, seems to especially suit wild field scabious, which in late summer forms a long strip of purple flowers marking out the route of the railway. This in turn attracts a beautiful proliferation of butterflies. The poorly-defined path along the railway peters out altogether before it reaches the motorway. The guide to Southrigg woods promises a continuation of path eastward alongside the How Burn to a car park near Balgornie Farm, however there doesn't seem to be sufficient people passing that way to maintain a clear route through the grass.

If you navigate around the many roundabouts of the Heartlands interchange, past the 21st century delights of Whitburn's McDonalds, KFC and Starbucks, before crossing the M8, there is a turn off to Balgornie Farm – home to a mountain of road planings and associated machinery. Part way along the road to the farm there is a lay-by that might have been installed to serve the footpath, However to reach it requires passing a succession of prominent signs proclaiming “No unauthorised entry”. A lot of effort seems once to have been invested into opening up Netherton and Southrigg woods so many can enjoy wonderful green places that have been shaped by a fascinating industrial history. It's regrettable that more people don't enjoy these pleasures, and particularly unfortunate that unnecessary obstacles seem to deter access from Whitburn.

See also

Route of the railway between No.1 and No.7 pits

Emerging from the reeds

Scaboius marking the route of the railway

Painted Lady butterfly on Scabious flowers

Red Admiral butterfly on Scabious flowers

Peacock butterfly on Scabious flowers

The railway route towards No.3 & 4 pits

Looking north towards No.1 pit, and the junction with the branch to Netherton pit.

Route of the railway - the long slope down to Greenrigg - site of the bogie incident - with route cut across by the M8

Imaginative map at the entrance to Southrigg woodlands

A chilly welcome at Balgornie