Shale Beneath the Runway - the Ingliston Pits

Ingliston, Hallyards

Associated pages: Ingliston No.33 pit, Ingliston No.36 & 37 pits

F19016, first published 14th April 2019

Many passengers landing at Edinburgh Airport enjoy a fine view of the shale bings that serve as a very obvious memorial to West Lothian’s industrial heritage. As the aircraft tyres touch down the tarmac however, few will be aware that deep beneath the runway, there was once a network of underground workings extending from the Ingliston shale pits.

As reserves of shale in the West Calder area became exhausted, Young’s Paraffin Light and Mineral Oil Company looked eastward for new supplies, and in 1891 leased the minerals of the Ingliston estate. They sank their No.33 pit on a site close to the river Almond near Lennie Muir and constructed a mineral railway that ran a mile and a half to the North British Railway’s South Queensferry branch. Other than a sharp curve and gradient at the junction with the NBR, this line followed an arrow-straight route across the flat carseland, crossing the main Edinburgh to Linlithgow road on the level near Boathouse bridge. Shale was carried in NBR trains to be retorted at Uphall oil works.

Plan from the contract between Young’s and the North British Railway, emphasising the dead straight route of the Ingliston branch, alongside the river Almond.

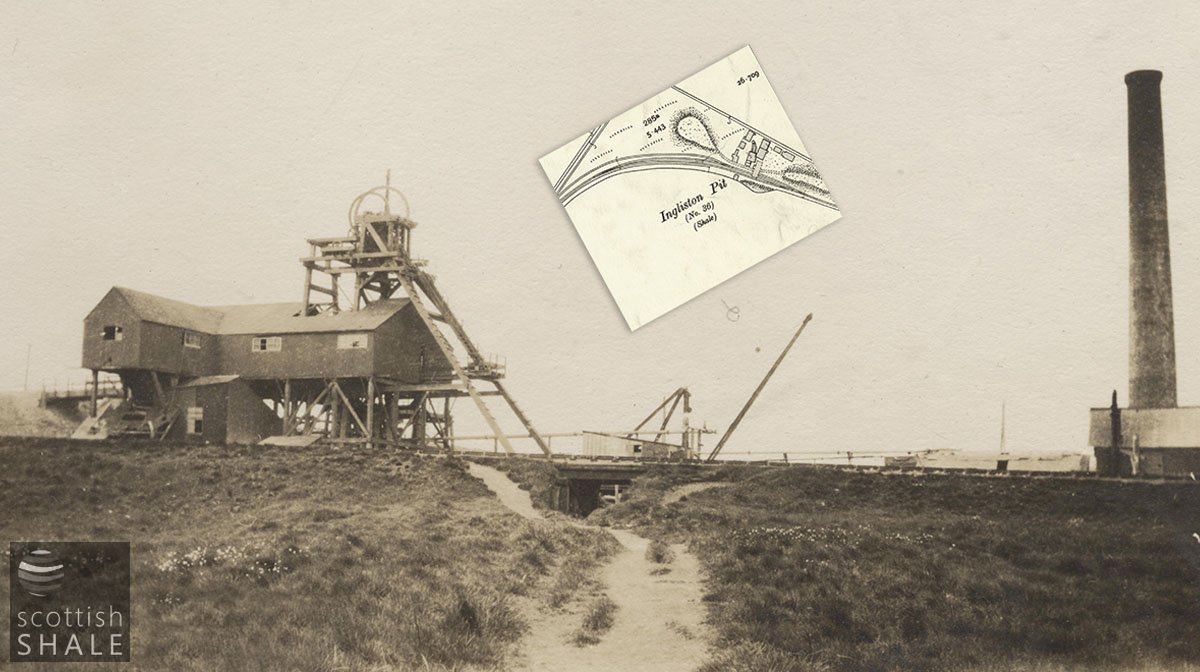

A photograph from our collection of an unidentified shale mine, probably photographed c.1920. The layout of buildings and shafts don’t precisely coincide with the layout of the Ingliston No. 36 & 37 pits shown on the OS map, – but it’s a close match?

Plan showing subsidence damage around Hallyards, with undermanager’s house beside the railway.

No. 33 pit began production of shale from the Dunnet seam in 1892, but soon encountered problems due to unstable ground and the increasing prospect that the river Almond might burst in and flood the workings. The pit was abandoned after only two years. Anxious to recoup some of their investment, Young’s continued to prospect on the estate and eventually located the Camps shale seam and much of the greater depth. In 1897, their Ingliston No.36 & 37 pits were sunk on a site about three quarters of a mile west of No.33, close to the existing mineral railway. With shafts extending to a depth of 366 feet, the new pits had few of the flooding problems that had been encountered at No.33, but were considered gassy mines, requiring special precautions when working. Deaths and major injuries from large blocks of shale falling from the mine roof also occurred with a sickening regularity.

At its peak, about 250 men were employed in the Ingliston shale pits; a few living in oil company housing at Lochend cottages, but the majority having homes in Kirkliston, Ratho Station, and Newbridge. Following world war one most of the Ingliston shale was diverted to the Dalmeny oil works for processing. Although this helped reduce transport costs, their distance from an oil works still placed the Ingliston mines at a disadvantage. Once the best of the shale had been exhausted, the Ingliston pits were abandoned in 1926.

Maximum extend of workings – from a mine abandonment plan.

Mined area superimposed on a modern aerial view

It seems that the ruins of mine buildings survived into the 1960’s and when plans to construct the current runway were promoted in the early 1970’s, the potential cost of stabilising the old mine works was put forward by protestors as one reason why the airport development should be sited elsewhere. As it was, plans for a central Scotland airport at Slamannan (?) never got of the ground, and Edinburgh got its international airport.

As might be expected, development of the airport obliterated most traces of mining activities, and has left a legacy of dead-end roads that dissolve when they reach the airport fence. The arrow-straight route of the old mineral railway now marks the northern boundary of the airport site, and the former mine locations now fall within the grassy margins of the runway. Other parts of the mineral railway have been ploughed-out or built over, leaving a shallow cutting near the site of Hallyards Castle, and some areas of subsidence in Hallyards wood, as the only evidence of the shale industry’s eastern outpost.

Take-off, photographed at close to the site of No.36 & 37 pits

Route of railway, looking east from the point that the line would have crossed the Hallyards to West Ingliston Road

Iron-stained pools beneath the trees of Hallyards wood - probably the consequence of mining subsidence.

A scatter of dressed stones is all that remains of Hallyards Castle, the 17th century mansion that would once have stood on a gentle mound overlooking the carselands. The ruined building was said to have been affected by mining subsidence and was demolished c.1929