Mysteries of the Moss

Railway and peat works in Easter Inch Moss

View from the Puir Wife's Brae, looking across the new bowling green and buildings of Kirkton Park. In the middle right of the picture, the West Calder branch swings off towards the right.

F17034, first published 23rd September 2017

The path across the moss between Easter Inch and Seafield, forming part of national cycle route No.75, provides a pleasant escape from motor vehicles that is enjoyed by cyclists, frantic fitness fanatics, and laid-back dog-walkers. Since the route was tidied up and surfaced twenty years or so ago, trees have grown up on either side of the path creating a green leafy corridor that obscures much of the true nature of the surrounding bog.

It would have been difficult to pass across this watery waste prior to construction of the mineral railway that now provides the foundation of the cycle path. This line, which served Seafield oil works for many years, followed a rather odd Y-shaped route and was known in railway circles, (rather oddly), as “the West Calder branch.” The origins of this mystery might lie in the railway politics of the 1870’s, when the North British Railway was locked in combat with its great rival, the Caledonian Railway, over access to the shale mining districts. In 1872, the NB applied for powers to construct a railway running west to east from Foulshiels (south of Whitburn) to Livingston Station, and a second running north to south from Easter Inch to West Calder, terminating at a station beside the Cleugh Brae. The two lines were to cross 580 yards north-west of Redhouse, very close to where the two forks of the Y-shape route still diverge. The N.B. abandoned powers to build the West Calder line in a deal that saw the Caledonian abandon equally silly proposals, however the route across Easter Inch to Redhouse, and a short part of the route heading eastward towards Livingston appear to have been built.

The railway will have initially carried traffic from the Seafield Patent Fuel Works, an enterprise backed by the Duke of Sutherland who in 1872 had experimented with using coal from his estate in Brora to produce oil, that was mixed with peat to produce fuel briquettes. From about 1873 these operations seem to have been transferred to Seafield where the lands of local MP John Pender provided all necessary ingredients. Briquettes were produced containing various combinations of peat, finely-ground coal, crude shale oil, ironstone dust and shale tar, but little market was found for this fragrant fuel intended for steam boilers and locomotives, and the company was wound-up in 1876.

It is not certain where the patent fuel works were located, but it seems likely that the same site was used for construction of the Seafield oil works, opened in about 1883, which was reconstructed in c.1892, and remain in operation until 1931.

From about 1912, Easter Inch moss, either side of the branch railway, was worked by the Midland Moss Litter Co. Ltd, who established a rectangular grid of peat-workings served by horse-drawn narrow-gauge tramways. Dried peat was milled and screened to produce a fine horticultural peat and a coarser moss litter used for animal bedding. The peat works continued to be served by rail when the rest of the branch was lifted following closure of the Seafield oil works, and remained in production into the 1950’s

From 1964 until his death in 1972, Norwegian peat and land reclamation specialist Anders Tomter, devoted his attentions to finding useful purpose for the disused peat workings at Easter Inch. Many experiments involved the mixing of spent shale and peat to create a productive soil. Little evidence of these efforts remain and today, as part of the Easter Inch Moss & Seafield local nature reserve, the focus is now on managing the area for wildlife by maintaining water levels across the bog.

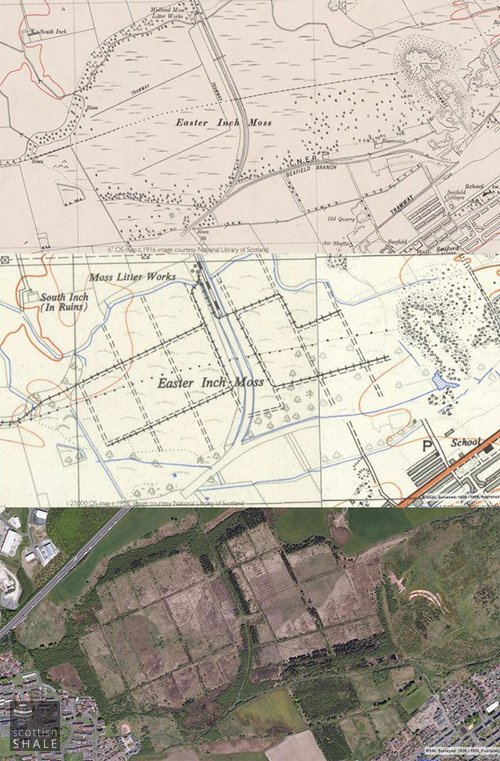

Above right: Maps from c.1938, showing the branch to the shale oil works still in place, and from c.1950 showing the branch cut short and narrow gauge tramways extending across the former trackbed to the eastern part of the moss.

The reed-filled peat workings, looking west towards Blackburn. The narrow-gauge tramway will have run along the heather-clad ridge.

Site of the moss litter works, which according to valuation rolls consisted of sheds, stable, power house and sidings, with surviving concrete floor slab of one of the buildings. The cycle-way runs between the trees in the background.

Broken remains of the granite memorial to Anders Tomter, set up beside the path at Easter Inch in 1974, and pictured c.1996 — with Reuben Chesters.

The fallen memorial, pictured c.1996 - does anyone know what happened to it?

The footpath pictured c.1996, before improvement and surfacing works, and when there was a clear view across the moss on either side.