Greendykes Bing and the Dirt Bike Boys

Whose bing is it anyway?

F21008 - first published 29th September 2021

Like Edinburgh castle, the Antonine Wall and Skara Brae, the Greendykes bing in Broxburn is a scheduled monument. This mighty heap of spent shale is rightly recognised as being of national importance to Scotland and is consequently protected from damage and development. While other shale bings have been removed or disfigured. Greendykes bing continues to dominate the landscape for miles around, and has become a source of pride and a symbol of local identity

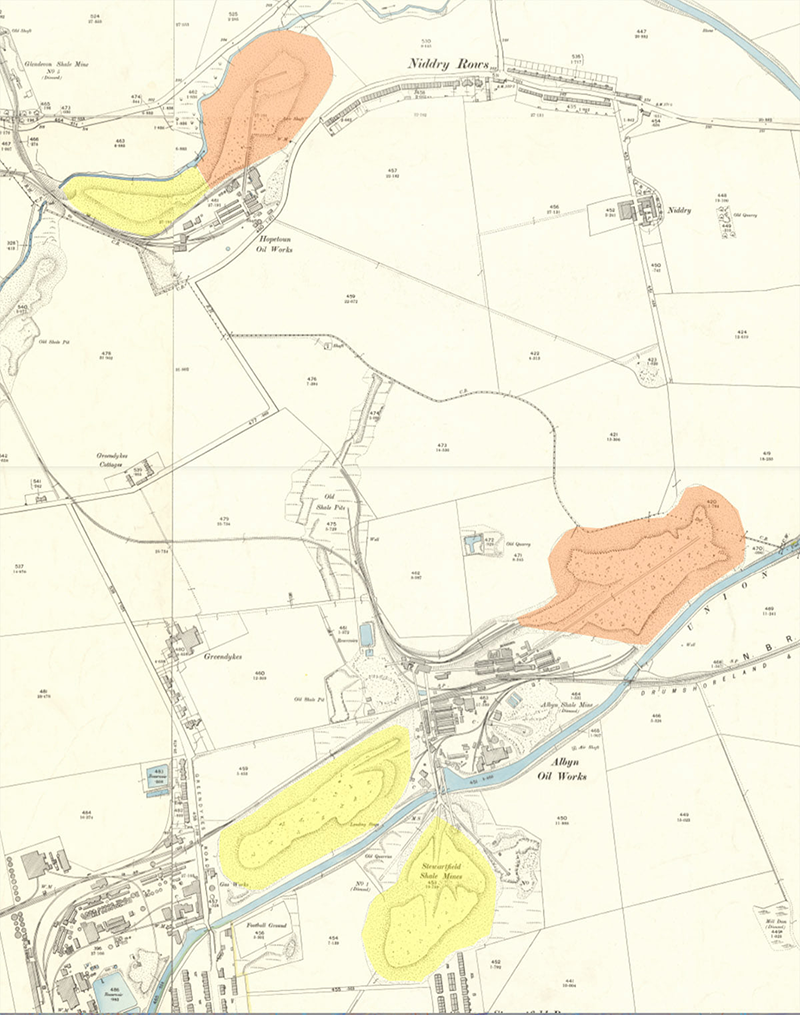

The name “Greendykes bing” is a modern invention. The great mountain of red blaes is in fact the product of two rival oilworks – the Albyn works of the Broxburn Oil Company and the Hopetoun works of Young’s Oil Company. The Albyn oil works, sited beside the canal in the lands of Earl of Buchan, was the first in the area. From the early 1860’s bings of waste shale first filled land to the west of works, then extended to the south at Stewartfield, and then was heaped-up to the east alongside the Union canal. When all other space was occupied, a new bing was begun that headed northward.

A little under a mile to the north, the Hopetoun oil works was opened in the 1870’s in the lands of the Marquess of Linlithgow. Once all of the land to the west, north and east of the works were heaped to capacity, a bridge was built beneath the Niddry road, and tipping began on lands to the south. Albyn bing stopped its advance north when the oil works closed in 1926, however the Hopetoun bing continued its journey south, eventually meeting and merging with its neighbour in the late 1930’s

It stops you in your tracks to think that every ounce of the mighty bing was extracted with picks and shovels in tunnels deep beneath the surrounding fields. These are man-made mountains created over a period of ninety years; the life’s work of several generations. Those who built the bings are now long-gone. Did they glance up at the towering peaks with a sense of pride and achievement? or did they curse the heaps of filthy waste that kept homes in a constant manky shadow?

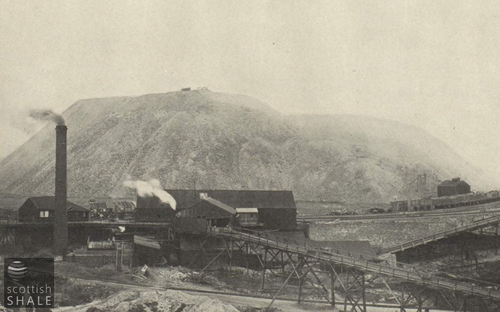

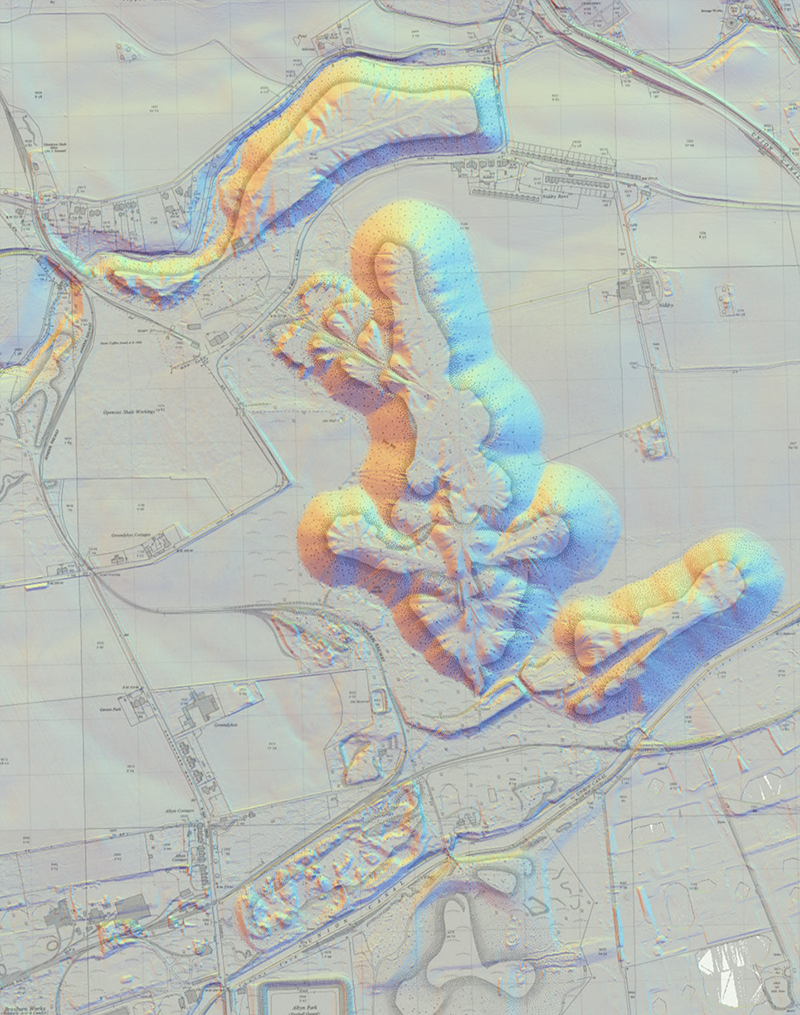

Bings were built up in a number of levels. Hutches of spent shale were hauled up a rope-worked incline to the level top of the bing, where each little waggon would be pushed along rails to the edge and manually up-ended to tip out the dusty contents. Every so often the rails would be moved, and a new lobe of tipped blaes would be created a little further along the edge of the bing. This formed a pattern of rails radiating towards the lobed edge of the bing, reminiscent of the outstretched fingers of a hand. Once that level top of the bing had been extended to the planned extent, the incline was extended upwards and material tipped to form a new flat top at a higher level, The series of steps formed in this way remain clearly evident either side of the routes of the inclined haulage leading up from the Albyn and from the Hopetoun oil works.

Most of the subtleties of these humps and hollows are invisible when standing on top of the bing and gazing at the landscape laid out beneath you. However modern LIDAR mapping detects small height differences to create wonderful images revealing a pattern of tramways and tipping points that have survived for over a century. The same technology also highlights the tracks and gullies cut into the face of the bing that were created far more recently through the use of trail bikes.

c. 1895 - the yellow areas are disused tips, the orange ones are in use. Maps courtesy of the National Library of Scotland.

c. 1914 - the yellow areas are disused tips, the orange ones are in use. Maps courtesy of the National Library of Scotland.

c. 1948 - the yellow areas are disused tips, the orange one is in use. The two bings have merged. Maps courtesy of the National Library of Scotland.

1960's map overlaid on a recent LIDAR image. Maps courtesy of the National Library of Scotland.

It must take tremendous skill and courage to charge full-throttle up the steepest face of the bing maintaining momentum of your bike just long enough to reach the safety of the summit. This scale of stunt is a real sport, requiring expensive equipment, all the protective gear, discipline and organisation. Not just a bunch of yobs messing about. It’s a dangerous pastime but other bikers are always at hand should something go wrong. These dirt bike desperadoes seem a courteous crew, although understandably camera-shy given their outlaw status

The northern part of the bing is still owned by Hopetoun estates, the southern parts are in now in Council ownership. Understandably, neither wishes to be responsible for such dangerous sport taking place on their property, and without formal consent of the landowner, off-road bikers are committing an offence under 34 of the Road Traffic Act 1988.

Dirt bikes are noisy anti-social machines that disturb the peace for miles around. Rightly or wrongly many associate bikers with all sorts of other nuisance. Without doubt, the action of trail bikes are slowly but irreversibly changing the shape of the bings by creating tracks and deep gullies that are gradually obscuring the subtle traces that contribute so much the heritage and meaning of this special place. This shouldn’t happen to a scheduled moment.

Many efforts have been made to prevent this. Neat signs prohibiting biking were quickly defaced or stolen, and fences were broken or by-passed. Within the last year or so, a deep ditch has been excavated between the bing and the Niddry road, creating a medieval-style defence that blocks the way for walkers but seems to provide little obstacle to resourceful trail bikers. It’s the worst of all worlds.

The red-blaes shale bing is (near enough) unique to West Lothian; something that is special and distinctive in an ever more homogenised world. As memories fade of the hardships and bad times of the shale industry, Greendykes bings is increasingly viewed as a proud monument to achievement rather than a hateful pile of waste.

From the top of this hard-won man-made mountain you enjoy a unique view across the landscape of the Lothians and gain a special perspective on its history. Reaching this lost plateau requires an energetic scramble up one of the gullies on the face of the bing, having first scaled the massive ramparts recently installed to exclude the bikers. Given the great significance of the bing, it seems remarkable that there are so many obstacles to accessing it. Would the residents of Edinburgh be equally accepting if they were prevented from climbing Arthur’s Seat?

Creating public access to the bing would be need to be approached very sensitively. The natural municipal-park, approach would be to round off the edges, tidy up the messy dangerous bits and cover everything with grass, much in the same way that Seafield bing was transformed into Seafield Law during the 1990’s. This would create a lovely public space, but would totally destroy all relevance and meaning to the scheduled monument – akin to giving the Mona Lisa a fresh coat of paint. But there must be ways in which flights of stairs or ramps can be built to provide access, and car parks and necessary infrastructure installed, without changing the character and value of this unique place. Such warts-and-all preservation would be form part of the charm and appeal of the monument, creating a special amenity for local residents, and a unique visitor destination.

As for the dirt bikers, it seems unsustainable that they continue to enjoy free rein of the entire bing, yet their sport deserves recognition and support. “Better to buy petrol than Buckfast” – as someone remarked on social media. Might one part of the range of bings be set aside and developed specifically for use by bikers and similar wheeled daredevils? Official sanction and necessary facilities would limit the most dangerous excesses, and skills might be built, and young talents nurtured without the regular need to play cat and mouse with the local police. And surely there’s some practical way of making bikes a little quieter so that the good folk of Broxburn can enjoy their Sunday morning lie-in?

Bing climbing can also be a spectacular spectator sport. Sitting on a sunny bing, watching the thrills and tumbles as successive riders power their way up 45 degree slopes, provides wonderful entertainment. Where else in the world can you see this? With a little imagination, wonderful things might be achieved.