Explosion at Oakbank

Locomotive explosion at Oakbank Oil Works

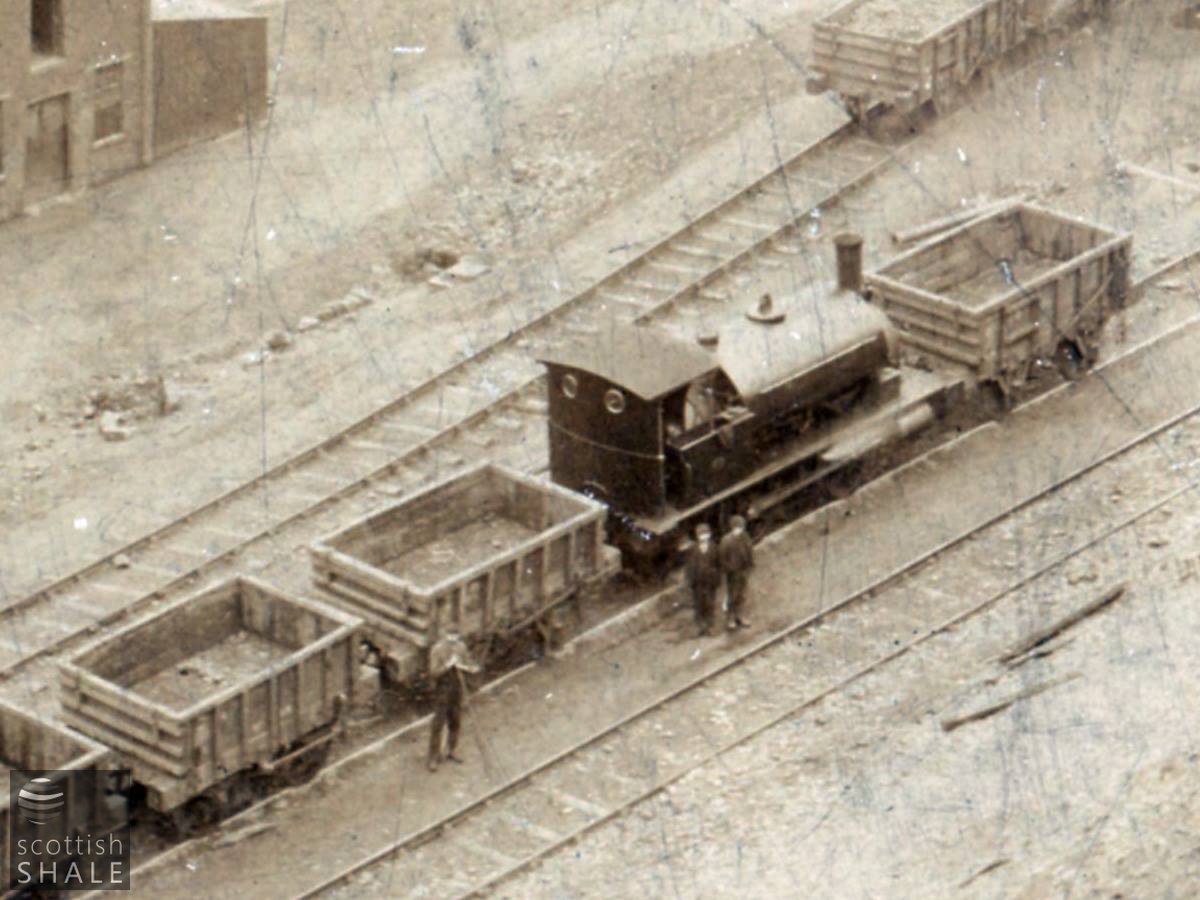

General view of Oakbank Oil Works from the bing, showing the works pug , empty shale wagons, and adjacent housing. The boiler explosion seems likely to have taken place in this area.

F18030, first published 7th July 2018

The Linhouse water cuts a deep glen through Calder Wood exposing a cross section of local rocks, including a rich seam of oil shale. This attracted the attention of early oil shale prospectors, and led to the construction of Oakbank Oil Works on a site beside the Caledonian Railway, about half a mile to the south. A private railway was built to supply the works with shale from various small-scale workings either side of the Linhouse water in the general vicinity of Hoghill farm. The village of Oakbank, housing the oil company's workers, grew up beside the railway line.

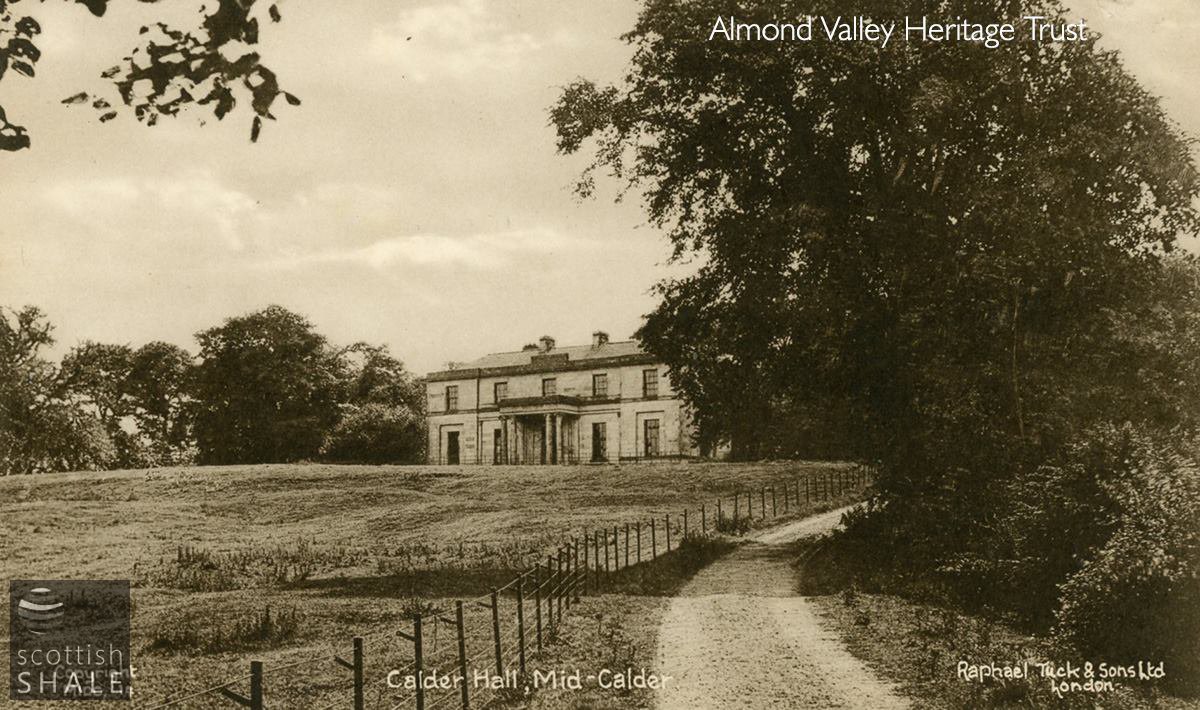

In 1865, or thereabouts, the vertical shafts of a new Oakbank pit were sunk near Midcalder to gain better access to the shale. The site of pit, about 200m east of the Midcalder bridge, lay on the opposite side of the Calder Hall estate from the railhead at Hoghill, and although landowner Stewart Bailey Hare was a director of the oil company, he had no desire to see trains of shale puffing through the parklands in front of his Greek revival mansion. Shale therefore had to conveyed along an inclined mine shaft beneath the lands of the estate before being loaded into railway wagons near Hoghill. It was not until 1885 that necessary permissions were obtained to extend the railway the full distance to Oakbank pit through the lands of Calder Hall.

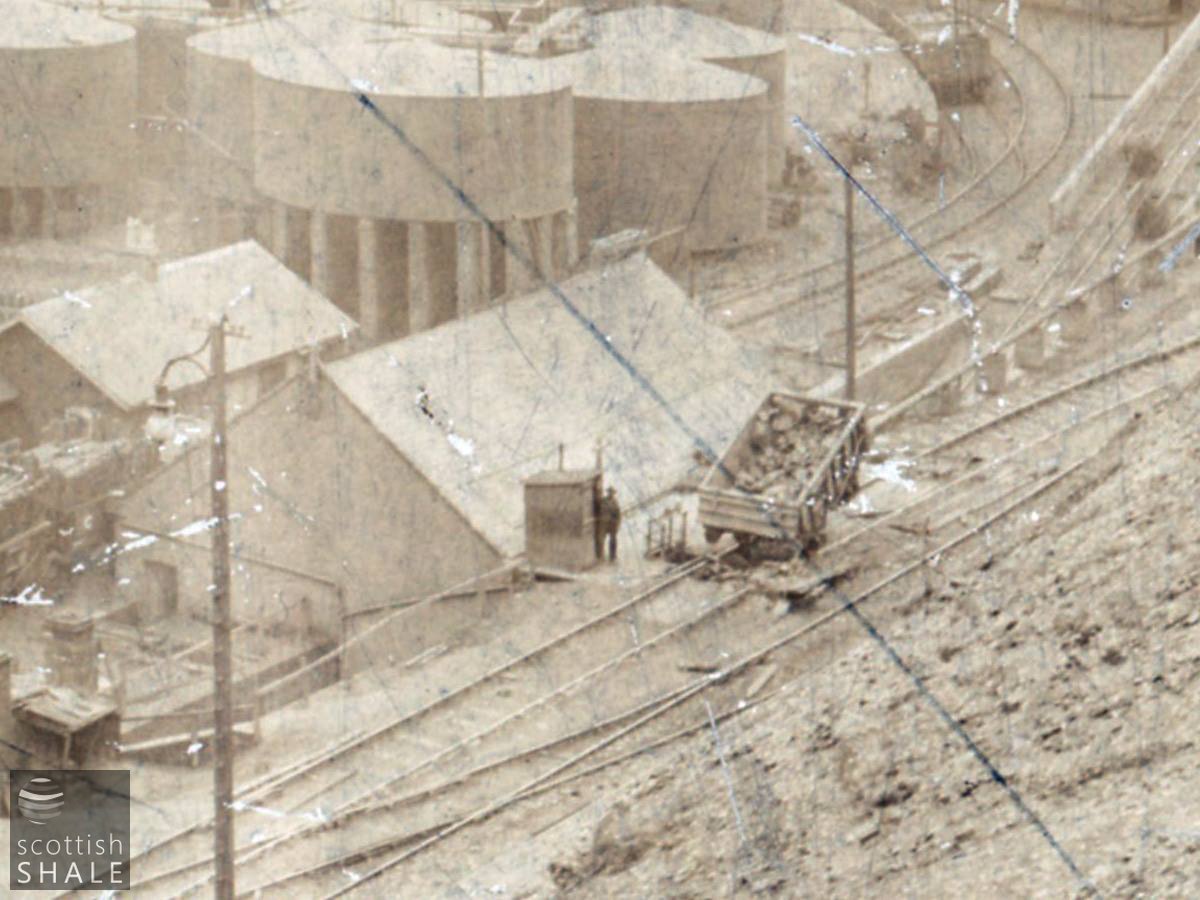

The railway at Oakbank pit. The loco also seems to be Oakbank No.3.

Calder Hall, and rather rough surrounding parkland c.1910. By that time the railway would cross the driveway behind the camera taking this image.

The oil company owned a number of small steam locomotives to work their railway. The first was bought prior to 1868 and at least one further pug engine was purchased during the early 1870's as evidenced by reference in company minutes to the need for a “new and more powerful locomotive with tender”. With the extension of the railway to Oakbank pit in prospect, a further loco was ordered in1884 from the Kilmarnock firm of Barclay & Co. After almost twenty years of hard service, this locomotive, and her crew, were to come to grief in a terrible accident.

At 9.15 on the 17th December 1902, the Barclay locomotive was being prepared for its days work at the weighbridge – a spot overlooked by much of the oil works and many of the houses of village. As the driver and fireman attended the fire and oiled up the machinery, the boiler exploded, killing both men.

1" OS map c. 1890, showing the private railway between Oakbank pit and Oakbank oil works. Image courtesy of National Libraries of Scotland.

Detailed layout of the works c.1895 from 25"OS map courtesy National Library of Scotland.

A Board of Trade enquiry was subsequently set up to investigate the cause of the accident. This revealed a deficiency in the stays that linked the copper firebox and the steel boiler-shell resulting in a catastrophic failure of the firebox crown. There was suggestion that this might have resulted form earlier damage caused by overheating, while it was also noted that those who had previously repaired the boiler were not familiar with its unusual construction; the manufacturers, Barclay & Co. being no longer in business. It was concluded however that neither the oil company, the boiler repairers, nor those responsible for inspecting and insuring the boiler could be held responsible for the unfortunate accident.

Newspapers reported the lurid details of the “two men blown to pieces”. The fireman, William Watts, was said to have been blown twenty yards “his head nearly having been blown into atoms”, while driver Thomas McKay was simply described as “much disfigured”. William Charles Watts was thirty one years old, sharing his home at No.75 Oakbank with his wife, a two year old son (also named William Charles Watts) and two lodgers. Driver Thomas McKay was a near neighbour at No.81, aged 35 with a four year old son. Such a public accident must have been a real blow to the close-knit community, and as reported in the local press, “the sad accident caused quite a sensation in the district”.

The A71 looking west towards the bridge over the Linhouse water. Once site of Oakbank oil works.

Route of the railway at the rear of Oakbank bowling club.

View from the riverside towards the site of Calder Hall. The railway once cut across this scene, although only a small part of the earthworks remain centre right.

Probable rout of the railway, through a grove of yew trees, close to Oakbank Mine.