Boring News from Gavieside

Investigations on the site of Gavieside No.40 pit

Abandonment plan, courtesy of British Geological Survey, showing the full extent of underground workings.

25" map c.1907, courtesy of National Library of Scotland.

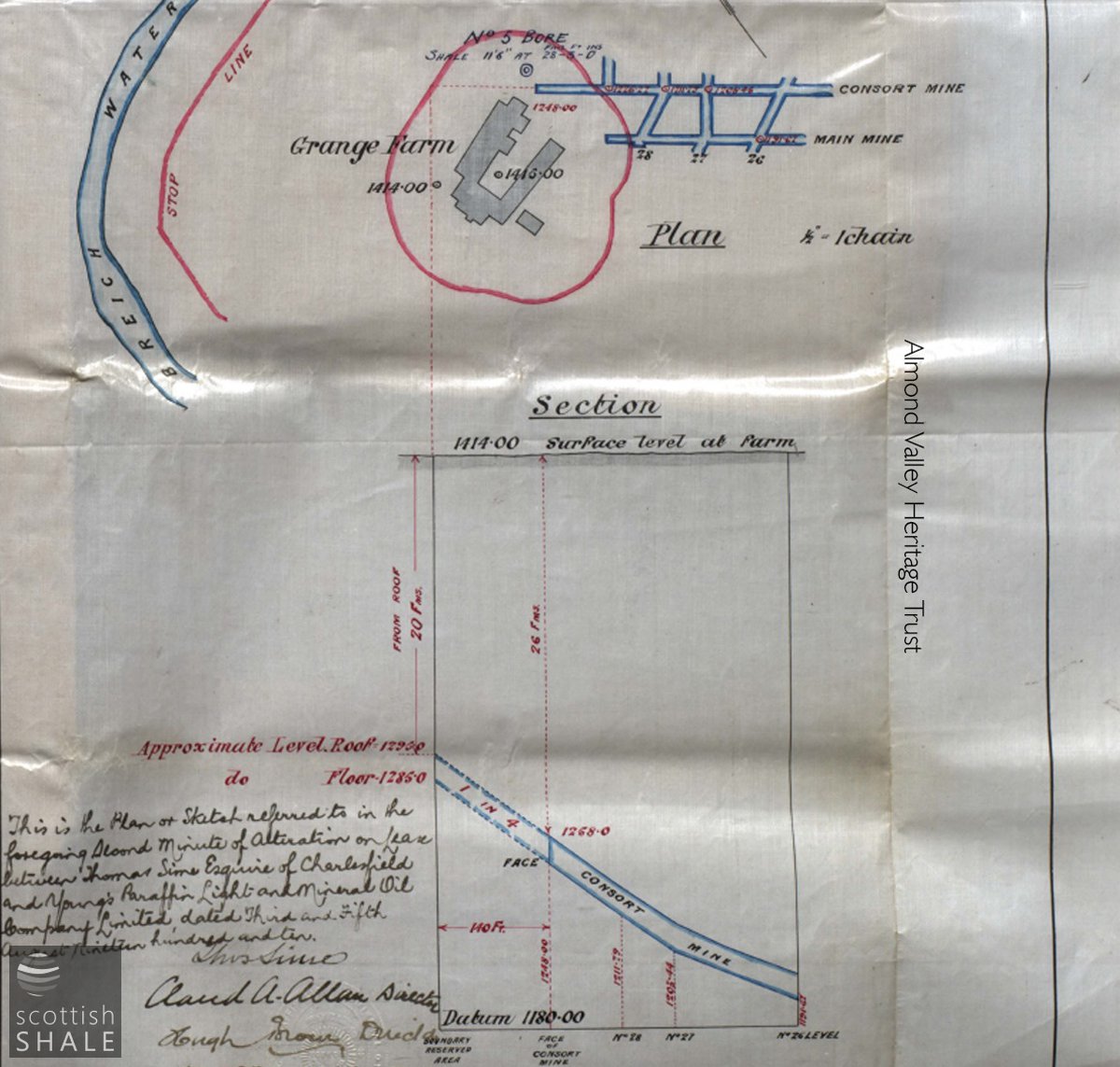

Plan and cross section showing seam rising at a 1 in 4 gradient approaching Grange Farm.

F19035, first published 16th September 2019

In recent weeks diggers was been excavating trial pits in the fields around Gavieside farm, and a dinky little caterpillar-tracked drilling rig has been trundling around, drilling test bores to explore the rock strata beneath.

During the shale mining era, this kind of prospecting work will have been carried out in the Gavieside area to establish the depth and location of seams of oilshale. The intention then would have been to give shale miners some idea of the geological conditions they were likely to encounter. The intention now is presumably to confirm the whereabouts of old oil shale workings so that provision can be made to prevent damage to new housing from mining subsidence. Within a few years, the open fields of the former Gavieside and Charlesfield estates will transformed by a major new housing development, extending from near West Calder to the Seafield road, providing homes for more than 2,500 people.

The surface buildings of Gavieside No.40 mine lay in the Gavieside estate, a little west of Gavieside farm, however the main mine workings headed north west into the Charlesfield estate, diving beneath the Fauldhouse to Livingston road in the direction of Grange Farm. The mine was opened by Young's Paraffin Light and Mineral Oil Co. in 1904, served by a new mineral railway linking to company's private railway at Polbeth, and onward to Addiewell oil works. The Dunnet seam of shale in this area was, on average, about ten feet thick and formed a basin, sloping steeply down into the ground from the mine entrance, levelling off then rising up again northward as it approached the River Almond. The contract between Young's Co. and the owners of the Charlesfield estate protected an area of shale beneath the buildings of Grange Farm, and the old toll house at Gunsgreen to avoid the risk of subsidence, and also prevented working less than 25 fathoms (45m) below the surface. Once the best areas of shale had been worked, Young's negotiated a revised agreement allowing mining up to 15m (27m) below the surface. At the northern limit of the working, close to the river Almond, working was discontinued in various places where mine plans showed “gravel”, or in some cases “sand” immediately above the shale seam. This suggests (rather alarmingly) that workings had reached rockhead and that only alluvial deposits lay above – perhaps a buried former course of the Almond.

Plan showing the early extent of the workings, showing the main roadways heading northwest and the exclusion zones around Grange and Guns Green.

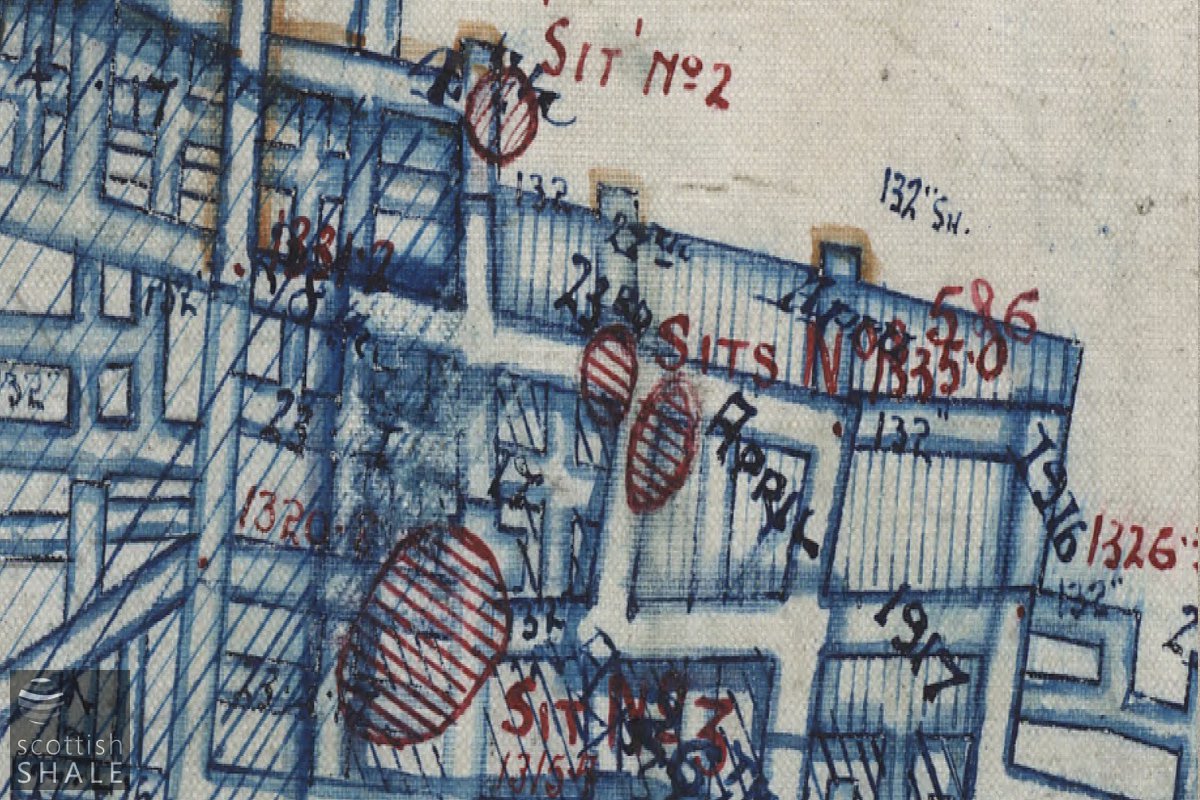

Close up of abandonment plan showing "sit" where the land surface has subsided - also the complex and beautiful arrangment of the workings.

Close up of abandonment plan, courtesy of British Geological Survey, showing the mine entrance, Dunnet shale workings (blue) and other (Raeburn?) workings in red.

Extent of workings shown on a modern map.

Workings seem to have reached their maximum extent in about 1917, following which the mine was stooped – removing the pillars of shale supporting the roof in the most distant parts of the mine and working back towards the mine entrance. Close to the Almond this working resulted in a number of “sits” where the surface of the ground collapsed into the underground workings. Young's were required to infill these and restore the land surface. Stooping was not permitted beneath the Livingston to Fauldhouse road for fear of subsidence. As the final phase of mining operations another seam of shale (probably the Raeburn shale) was worked in an area around the mine entrance, but at a higher level in the ground. Subsidence of these workings is probably the cause of the irregular surface of the field near Gavieside immediately south of the road.

Fatal accidents were once an accepted part of mining life and No.40 pit was the scene of at least two deaths. In 1909, George Beattie from Mossend was killed when a rake of hutches broke away on an incline below ground; he was knocked down and run-over by five hutches. In 1926, in the final days of the mine, John Brown Martin of Livingston Village died in a roof-fall. There were also happier moments, when mine staff won awards for the humane treatment of the pit ponies that worked in the mine. The exhausted mine was officially abandoned in 1927, but it seems to have been several years before the pit bing and other ruins were cleared and the area returned to agriculture. Unfortunately no photos of the mine buildings are known to have survived.

Today, much of the former lands of Charlesfield forms one large open field with a curiously dog-legged farm track passing across it – an echo of 18th century field boundaries. It's odd to think that all this will soon all be houses.

Early morning site investigation near Gavieside Farm, with an iconic backdrop. September 2019.

The "big field" of Charlesfield. The area of "sits" lie beneath the woodland behind the tractor.

Site of trial pits near Gavieside farm, with Polbeth in the distance.

One of the last harvests in the big field?

The big field beneath which miners from No.40 mine will have worked. Looking towards the Cauldstane Slap.

The road to Charlesfield House once continued across the stubble field to the left, past the long vanished "Wilkie's Wood".

The buildings of Grange Farm were protected from mining operations.