On the Bing, waiting for the Bomb

A Royal Observer Corps post in West Calder

F19046, first published 31st December 2019

From the top of Hermand oil works bing you can enjoy a panoramic view across the Firth of Forth to the green fields of Fife, past the Bathgate and Ochil hills, and beyond to the Highlands of Perthshire. In the advent of a nuclear attack, the site might provide a grandstand view of the destruction of Scotland's capital, the conflagration of Grangemouth, and mushroom clouds on the western skyline marking the end of industrial Lanarkshire. It is with prospect in mind that the bing was chosen, in 1959, as site for construction of a Royal Observer Corps monitoring post.

The Royal Observer Corps was a volunteer organisation formed in 1925 to serve as “the ears and eyes of the air force”. During the second world war they played a vital role in reporting enemy aircraft movements, but in a subsequent age of radar and high altitude jets, they could make little useful contribution to defence and plans were drawn up to disband the organisation. However, with the growing prospect of nuclear conflict, a new role was found for the Corps. Rather than spotting aircraft, they were tasked with front-line reporting in the advent of a nuclear strike. From 1956 a network of almost 1,500 underground monitoring posts were built throughout the length and breadth of Britain. West Lothian received only three posts; the West Calder ROC post on top of Hermand bing, close to the West Calder to Harburn road, the Bathgate ROC post near Crosshill Drive, and the Bo'ness ROC post near the club house of the West Lothian golf club. These were all part of the ROC No.24 group, whose HQ were in a bunker beneath RAF Turnhouse.

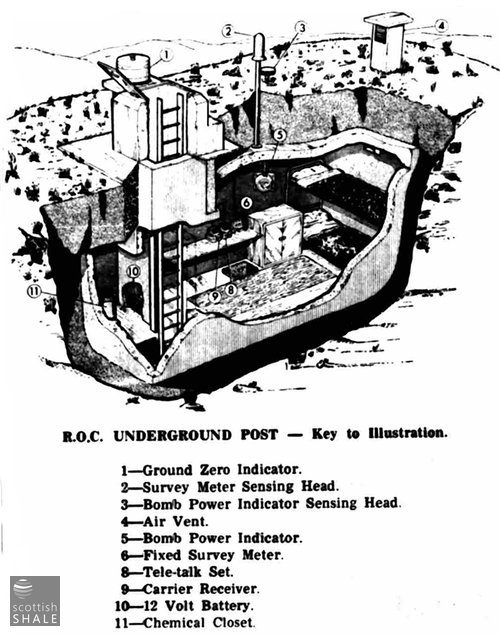

Each monitoring post consisted of a small room within a reinforced concrete box, covered by at least three feet of soil and accessed through a manhole and a 19ft long vertical steel ladder. This was intended to provide some protection against a nuclear blast and reduce exposure to radiation. Little showed about the surface other than filter equipment to cleanse incoming air and various pieces of monitoring equipment. At times of threat, the posts were manned by part-time volunteers of the ROC, who were issued with a uniform and paid a nominal fee for the time spent at their post. Recruitment advertisements portrayed membership of the corps as suitable for “men and women between the ages of 16 and 60 who are looking for an interesting, worthwhile hobby”.

East post was equipped with bunk beds, a chemical toilet and had ration packs “containing biscuits. steak and kidney pudding, tea, sugar, milk, etc. which would sustain three men without contact with the outside world for three days.”

In the event of a nuclear attack, the monitoring post would report levels of radiation, other measurements, and readings from the “ground zero indicator”. This was little more than a drum lined with photographic paper which some poor soul would need to emerge from the bunker to retrieve. When developed, this provided an indication of the intensity and direction of the blast.

We should be eternally thankful that none of these systems and contingency plans were ever tested in anger. Following the fall of Berlin Wall and the removal of the soviet threat, the ROC were disbanded in 1991.

Today many ROC observation posts survived locked and forgotten in remote parts of the country. The West Calder post was abandoned in 1991, and in 2005 it was still possible to climb down into the bunker and survey a scatter of papers and furniture, while a portrait of Her Majesty the Queen smiled calmly down from the wall. Since then, much of the spent shale has been quarried away, and for number of years the exposed sides of the concrete room hung perilously at the edge of the bing. The concrete box now sits, almost upside down, at the foot of the bing; a monument to a horror which thankfully never arrived.

The scene in 2011, with the underground room still clinging to the edge of the bing.

The road to Hermand bing, and the concrete room.

The underground concrete room, now exposed.

The underground concrete room, now exposed.

Once the buried top surface of the underground room, with air pipe and services.

An intact ROC post, near Dornoch, photographed last year.