Creed oil works

Throughout the 1850's, various men of business and science attempted to manufacture mineral oils by heating organic materials such as coal, shale, timber or peat. At the same time that James Young was perfecting his method of making oil from coal at his secret works in Bathgate, experiments were taking place near Stornoway, on the Isle of Lewis, to manufacture paraffin oils from peat.

James Matheson, a native of Lairg in Sutherland, made his fortune in the tea and opium trade with China. In 1847, following his retirement from this dubious business, he purchased the Isle of Lewis, and invested large sums to improve the amenities and economy of his new domain. At that time, grand schemes were afoot to establish new industries in a famine-struck Ireland, including fanciful dreams of an “Irish California” in which layers of peat would be stripped off for the manufacture of oils and waxes, leaving behind fertile agricultural land. Although little progress was ever made with these ill-considered plans, they may have inspired James Matheson to consider what value might lie in the deposits of peat that blanketed much of the Isle of Lewis.

Henry Caunter, a Devon businessman and associate of James Matheson was put in charge of an enterprise to extract oils from peats of Lewis, joined in 1858 by chemical engineer Dr Benjamin Paul. The following year, construction began on the “Lews Chemical Works” at Creed; sited on moorland a little to the west of the Matheson's Lews Castle estate, and close to a small building known as the candle works, where initial experiments had taken place. There appear to have been many setbacks (including the odd explosion) in developing this new technology, but most were overcome by 1862 when Dr. Paul published a full description of the works.

Peat was transported from the peat banks by a network of tramways, wagons being “propelled by steam” (presumably with a haulage cable) or by sail “when the wind is favourable”, The rails ran along the top of the kilns, allowing peat to be discharged directly into two banks of five egg-end furnaces, each holding about two tons of peat. The hot vapours produced by the controlled burning of peat were cooled and condensed to form an oily tar, which was separated from water in tar ponds. This ammonia-rich water was reacted with crushed sea shells to produce ammonium sulphate fertilizer. The process was generally similar to that later adopted by the shale oil industry. The greatest challenge to efficient working was the variable wind conditions that affected the draught through the furnaces and consequently the yield of tar. This was eventually controlled by use of a steam powered fan. Most of the oily tar produced was carted through Stornoway to a refinery at Garrabost, six miles to the east, although some of this crude product was used with minimal processing as grease, or anti-fouling paint.

The works were always considered rather a novelty, and various descriptions were published in national newspapers; one account of 1865 describing it as “a curious monument of advanced chemical science, in a remote region, where civilisation itself is a novelty.” ........... Tar production continued until about 1874 when – like so many Scottish oil works - operations finally succumbed to competition from cheap imported American oils. Plans were considered to convert the works to supply Stornoway with gas, but the equipment was finally dismantled and sold off as scrap in 1877.

Donald Morison – described in one account as “the intelligent foreman at the Creed works” - was intimately involved with the plant from its erection to it's dismantling. He left a diary that not only provides detailed description of practical arrangements, but also gives great insight into the personalities associated with the enterprise. His words describe the accidents, misjudgements, intrigue and occasional dishonesty behind this great adventure. In his book “An Enormous Reckless Blunder”, author Ali Whitford draws on the diaries, along with much other research, and a deep local knowledge, to expertly tell this fascinating story.

In recent years an interpretative panel has been set up in the car park close to the River Creed, and a path signposted to the site of the Creed works. A tombstone-style memorial has been set up on a rocky outcrop overlooking the site of the kilns and condensers.

Little has significantly changed in this landscape over the last 140 years, other than the continued build-up of moss that is slowly obscuring the ridges and hollows left behind by this industry. The routes of tramways can still be clearly made out, but the area thought to have been the site of the works is more difficult to interpret, hindered by the absence of detailed maps that show the original layout. The rectangular outline of a small building, now curiously carpeted in blue speedwell, is still clearly evident. If correctly identified as the ruins of the experimental candle house set up in about 1856, it represents one of the earliest surviving relics of oil industry in Britain.

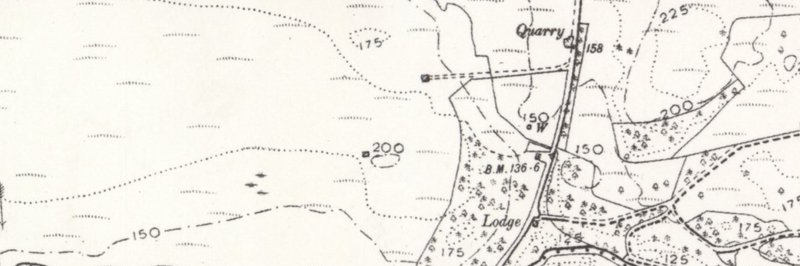

6" OS map c.1899, courtesy of National Library of Scotland. The 1899 OS shows none of the tramway earthworks and other features of the site that would have existed at that time, providing little indication of the original layout. Two small structures are shown; one corresponding to the "candle works" thought to have been the original experimental works, the other perched on top of a rocky outcrop to the south of the works - a logical place for a chimney. One account describes that a 30ft high chimney was sited on a hill 50 yards from the works.

6" OS map c.1899, courtesy of National Library of Scotland.

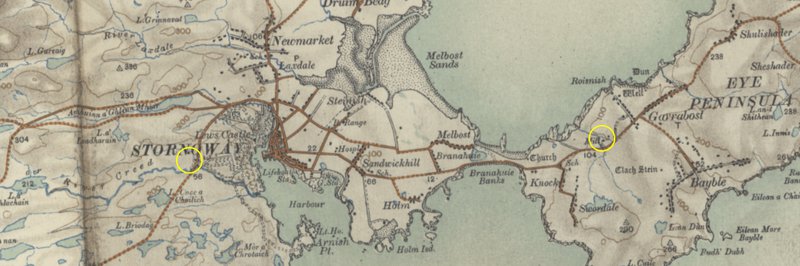

Half inch OS map c.1910, courtesy of National Library of Scotland, with location of Creed and Garaboost works marked

Recent images

6th June 2019 - Looking westward, the fence marks the route of the road to the original candle works. The wet area marks the likely site of the tar ponds.

6th June 2019 - A rectangular area carpeted in blue speedwell marks the outline of the original "candle works" building.

6th June 2019 -The memorial perched on a rocky outcrop. To the right the folded green landscape is thought to mark the site of the Creed works where tar was once manufactured from peat.

6th June 2019 - A green embankment to the north of the works might mark the route of a tramway, or perhaps the course of a flue

6th June 2019 -

6th June 2019 - Car park interpretation.

6th June 2019 - An impromptu museum of found objects beside the memorial. A brick, a piece of wrought iron which might have been a rail, and a broken piece of cast iron firebar.

6th June 2019 -

6th June 2019 -

PEAT PARAFFIN MANUFACTORY IN STORNOWAY

The Skye correspondent of the Inverness Courier writes as follows :- Having procured a note of introduction to Mr. Caunter, the constructor and manager of the Paraffin Works, I set out for them; but on my way there I was much taken with the improvement of the land about the town, so that within a radius of a mile or more it looks more like a low country district than as I saw it long ago, all bogs and gravel knowes, and but little of it cultivated, and still less of it enclosed. It is now all laid out in moderately-sized parks, in which I observed a long mound of manure, made out of the offal of the herring of the season, and of moss or earth, serving the double purpose of clearing the shore and town of that garbage, and contributing at the same time to the lands fertility. Arrived at Mr. Caunter's residence, I found him to be an Englishman, with the bluff, ready, off hand manner of his countrymen, very civil, attentive, and communicative.

We set out to the works at a place called the Creed, where the first part of the process is carried on, and where an extraordinary number of peat-stacks are seen arranged on both sides of an iron tramway, on which waggons are placed and filled, and then hauled to the works by steam power. When the wind is favourable sails are set on the waggon's to hasten their progress. About four to five hundred pounds a year is paid to work people for cutting and securing these peats; there being about 800 irons of them cut at 11s, 6d, the iron. An iron of peat is what a peat-iron will cut in one day when kept going all day, and when it is expected here at least to cut 75 solid yards of peat-moss. Arrived at the works, the peats are turned into the furnaces where they are consumed, their bulk immensely reduced and the tar extracted. The smoke from the peat is all consumed in the process, and several furnaces are kept going by gas alone produced from the peats in the process. One little disc was pointed out to me which resolved at the rate of 1800 turns in the minute; these revolutions could not of course be counted, but they could easily be calculated from knowing the circumferences of several wheels by which it was moved.

Glasgow Herald, 11th November 1865

.......

The Lewis Chemical Works, where there is carried on a manufacture of paraffin oil from peat. The first process is carried on at a place called The Creed, where peats are cut, and by a process of distillation, a kind of tar is extracted from the smoke. The tar is then carried a distance of six or seven miles to Garrabost, where it undergoes another process, conducted by steam machinery, and ultimately paraffin oil and paraffin itself are produced

There are also lubricating oil and grease manufactured, the latter is used for coating ships' bottoms, and termed " anti-fouling grease," and has proved itself far superior to anything yet used for this purpose. This great undertaking originated with Sir James Matheson, for the purpose, if possible, of converting the large tracts of moss in the Island to some useful purpose, and ultimately to cultivate the land when thus cleared. A great amount of money is embarked in this undertaking, and is a source of employment to a large number of people, there being at present about sixty men constantly employed, besides a larger number who get employment in summer in cutting and drying the peats.

Slater's Royal National Commercial Directory of Scotland for 1878